The History Behind A Soldier of Substance by D.W. Bradbridge

/Unless you are either an expert on the English Civil War or were brought up in the town of Ormskirk in Northern England, it is unlikely that you will have ever heard of Lady Charlotte de Tremouille, the Countess of Derby.

In itself, this is perhaps not surprising, for, in the grand scheme of things, her role in the Civil War was of minor importance both strategically and politically. Nonetheless, the dramatic nature of her valiant defence of Lathom House during the Spring of 1644 with only three hundred men against a vastly superior parliamentary force, is a story well worth telling.

Not that I am the first to think this. Until the end of the 19th century, the tale of Lady Derby’s exploits retained a much more prominent position within the British national consciousness, spawning a number of popular books and poems, just about none of which have stood the test of time. The best known of these is William Harrison Ainsworth’s novel The Leaguer of Lathom.

Historically, it suited many of those writing about the siege to portray Lady Derby as a defenceless woman, who loyally defended her husband’s house against evil and heartless oppressors, as this fitted in closer with prevailing views on morality and the role of women. It is, however, clear that Lady Derby was nothing like this. She was clearly a woman of steel with impressive negotiating skills, who proved herself able to run rings round the parliamentary officers with whom she crossed swords. In his 1991 book on the siege To Play the Man, Lancashire historian Colin Pilkington describes her as being ‘as devious as Elizabeth I, as inflexible as Mrs Thatcher and with the physical presence of an Amazon.’ Lady Derby, who was a granddaughter of William of Orange (William the Silent) and a cousin of Prince Rupert, was most certainly not a woman to be trifled with.

Lady Derby’s strength was certainly recognised at the time of the siege. She was eulogised by those on the royalist side, and readily compared in the newssheets with her husband, the Earl of Derby. The Perfect Diurnall, for example, described her as being “of the two a better souldier”, whilst the Scottish Dove newspaper famously pointed out that she had “stolen the earl’s breeches”.

Most of the eye witness accounts of the siege were written by royalists, so it is easy to be misled. However, the overriding impression given by these documents is of a supremely confident woman holding court, whilst being ably aided by a team of efficient professional soldiers and wise strategic advisors, such as her personal chaplain Samuel Rutter, who was responsible for fooling the besieging forces into thinking that the thing Lady Derby most feared was a siege, whereas the Countess was perfectly well aware that only a direct assault on the garrison would be likely to succeed. It is no surprise that Sir Thomas Fairfax, initially in charge of the siege, and notoriously unable to deal with women in the strict manner necessary in a military negotiation, took the first opportunity to return to Yorkshire, leaving the siege in the hands of the inept Colonel Alexander Rigby.

Over the last hundred years, the details surrounding the First Siege of Lathom House (there were, in fact, two sieges) have gradually drifted into the backwaters of history. This is a shame, because the events which took place between March and May 1644 make up a captivating adventure story. Given the abject incompetence of the parliamentary forces at times, they would also, in my opinion, form the basis for an engaging comedy film – but that is another story. In any case, I make no apologies for purloining this piece of history as the basis for A Soldier of Substance.

About the D.W. Bradbridge

D.W. Bradbridge was born in 1960 and grew up in Bolton. He has lived in Crewe, Cheshire since 2000, where he and his wife run a small magazine publishing business for the automotive industry.

“The inspiration for The Winter Siege came from a long-standing interest in genealogy and local history. My research led me to the realisation that the experience endured by the people of Nantwich during December and January 1643-44 was a story worth telling. I also realised that the closed, tension-filled environment of the month-long siege provided the ideal setting for a crime novel.

“History is a fascinating tool for the novelist. It consists only of what is remembered and written down, and contemporary accounts are often written by those who have their own stories to tell. But what about those stories which were forgotten and became lost in the mists of time?

“In writing The Winter Siege, my aim was to take the framework of real history and fill in the gaps with a story of what could, or might have happened. Is it history or fiction? It’s for the reader to decide.”

For more information please visit D.W. Bradbridge’s website. You can also find him on Facebook and follow him on Twitter

About A Soldier of Substance

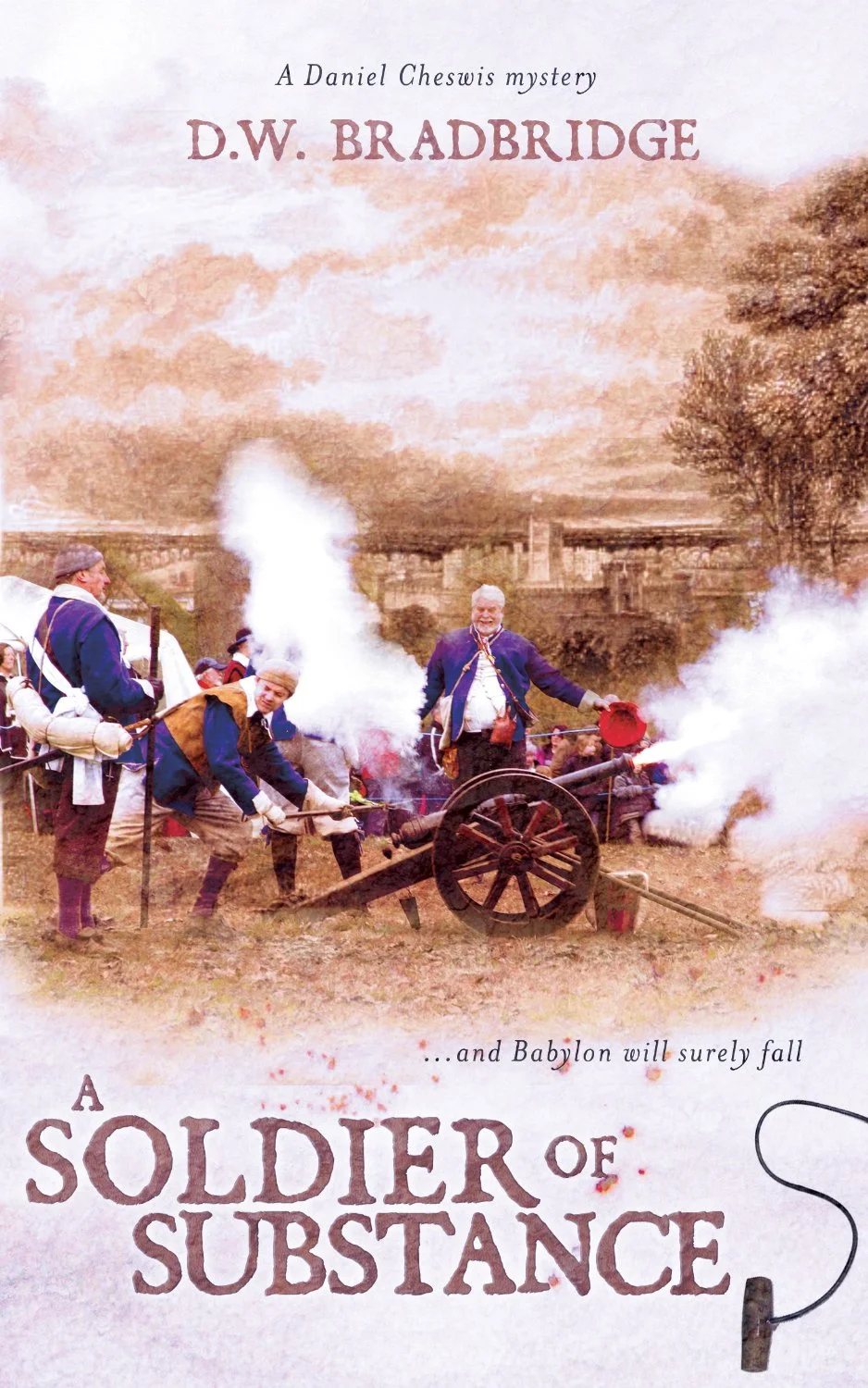

1644. The smoke of parliamentary musket, cannon, and mortar fire is in the air around the royalist stronghold of Lathom House. Though guards still stand atop its walls, it is besieged on all sides, and it is only a matter of time until the house, along with its embittered and unwavering countess, Lady Charlotte de Tremouille, falls to Parliament’s might. Yet somehow, a royalist spy still creeps, unseen, through its gates, and brings the countess Parliament’s secrets.

Barely recovered from the trials of the last few months, Daniel Cheswis is torn from his family and sent north, to uncover the identity of the traitor; though before he can even begin, Cheswis finds himself embroiled in a murder. A woman has been garrotted with cheese wire in her Chester home, suggesting there is more than just the usual hatreds of war at play.

As lives are lost and coats are turned on both sides, Cheswis is tasked with finding the murderer, uncovering the traitor, and surviving his soldierly duty long enough to see Lathom House fall.