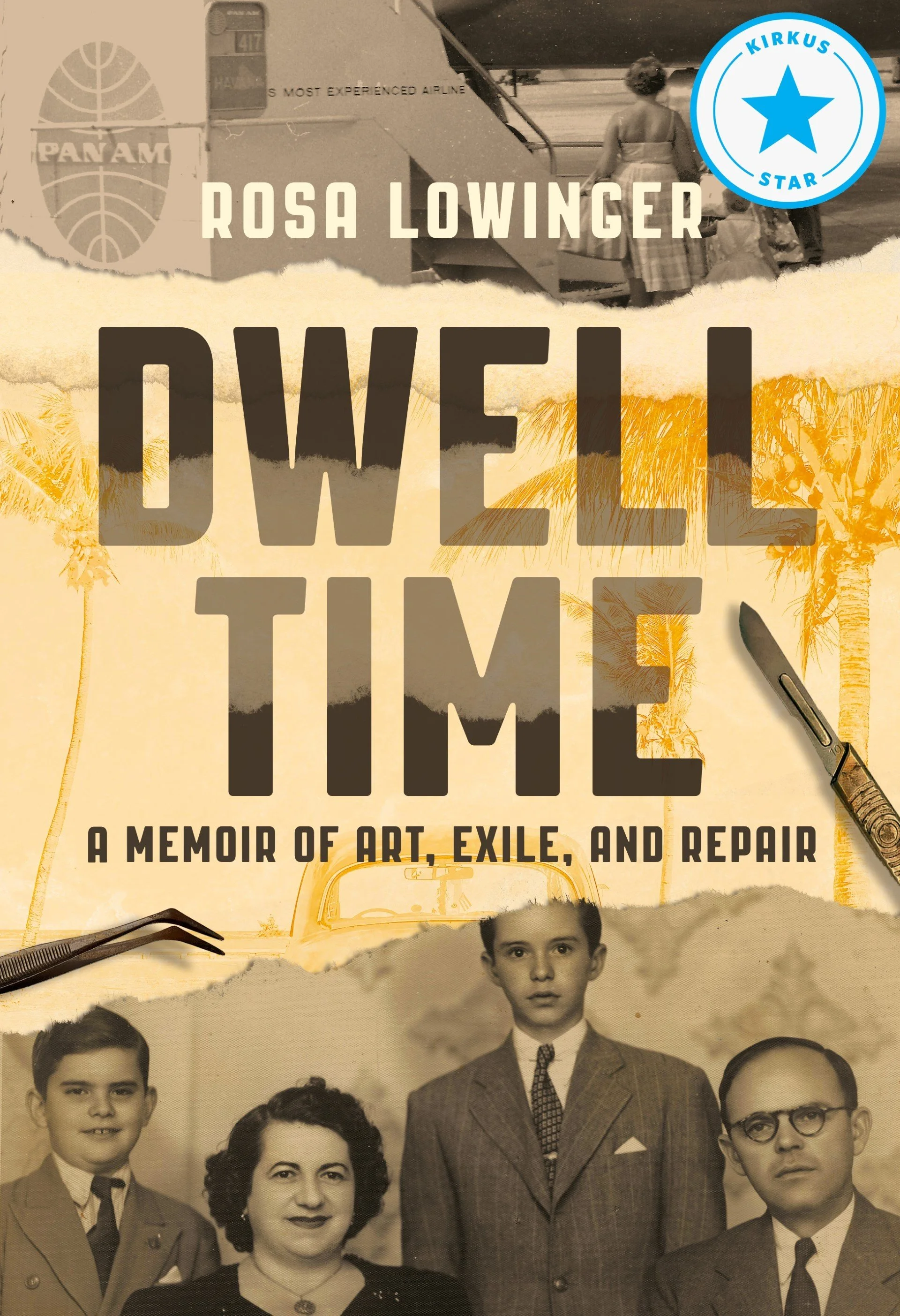

Spotlight: Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair by Rosa Lowinger

/Dwell Time is a term that measures the amount of time something takes to happen – immigrants waiting at a border, human eyes on a website, the minutes people wait in an airport, and, in art conservation, the time it takes for a chemical to react with a material.

Renowned art conservator Rosa Lowinger spent a difficult childhood in Miami among people whose losses in the Cuban revolution, and earlier by the decimation of family in the Holocaust, clouded all family life. After moving away to escape the “cloying exile’s nostalgia,” Lowinger discovered the unique field of art conservation, which led her to work in Tel Aviv, Philadelphia, Rome, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Charleston, Marfa, South Dakota, and Port-Au-Prince. Eventually returning to Havana for work, Lowinger suddenly finds herself embarking on a remarkable journey of family repair that begins, as it does in conservation, with an understanding of the origins of damage.

Inspired by and structured similarly to Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, this first memoir by a working art conservator is organized by chapters based on the materials Lowinger handles in her thriving private practice – Marble, Limestone, Bronze, Ceramics, Concrete, Silver, Wood, Mosaic, Paint, Aluminum, Terrazzo, Steel, Glass and Plastics. Lowinger offers insider accounts of conservation that form the backbone of her immigrant family’s story of healing that beautifully juxtaposes repair of the material with repair of the personal. Through Lowinger’s relentless clear-eyed efforts to be the best practitioner possible while squarely facing her fraught personal and work relationships, she comes to terms with her identity as Cuban and Jewish, American and Latinx.

Excerpt

DWELL TIME: A Memoir of Art, Exile and Repair By Rosa Lowinger

© 2023 Published by Row House Publishing, October 10, 2023. All Rights Reserved.

Pages 46 - 51

I was born three months before Fidel Castro, his brother Raúl,Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and fifty-seven other would-be revolutionaries left the Yucatan bound for Cuba on a yacht that was designed to hold twenty people and whose name was Granma, a misspelling of the word Grandma. Recounted in books, newsreels, and magazines, the events of that period are the stuff of opera: A storm throws the Granma off course. The landing is ambushed by the dictator’s army. The Cuban press deliberately misreports that the revolutionaries were all killed or captured. Then, finally, a clandestine visit by New York Times reporter Herb Matthews to the Sierra Maestra Mountains, where he reveals that the swaggering, cigar-smoking Fidel Castro is very much alive and in the throes of a full-scale guerrilla war.

Described as the best journalistic scoop of the twentieth century, Matthews’s front-page story appeared on February 24, 1957. I was almost five months old then—the second generation of my family to be born in Cuba. That I would be the last would have seemed as absurd a notion to my parents as a spaceship landing on the moon. What on earth could have wrenched us away from this prosperous, welcoming country? Though Cuba was ruled by the same white Catholic elite that had brought the world the Inquisition, Cuba’s bigotry in the mid-twentieth century was reserved for its population of color, not Eastern European whites. Racism in prerevolutionary Cuba was so pernicious that even President Batista, of mixed race, was not allowed to join the Havana Country Club. This fact was, of course, lost on people like my family, who only noticed that our fellow Cubans, whether Black or white, took no issue with our religious beliefs.

Eastern European Jews—Ashkenazis—were generally referred to as “Polackos,” or Poles. That was not viewed as a slur, just Cuban shorthand, a moniker like “Chino” for Asians, “Gallego” for Spaniards, and “Alemán” for anyone not Jewish from a German-speaking country. Violence toward Jewish people, as had been seen during the war and its horrific aftermath, when

emaciated concentration-camp survivors returned to towns in Hungary, Ukraine, and Poland only to be met by murderous mobs, simply was not prevalent in the Caribbean.

There were exceptions. Most notable among them was the St. Louis affair, a devastating 1939 refusal by then-Cuban president Federico Laredo Brú to allow an ocean liner carrying nine hundred Jewish refugees with proper visas to disembark at Havana. The boat was also turned away by Canada and the United States, resulting in the death of a third of the passengers and harrowing escapes for those who managed to elude capture by the Nazis. My mother recalls marching on the presidential palace as a child with all the island’s Jewish students, the residents of the Froyen Farayn among them, waving Cuban flags to protest the decision.

By the mid-1950s, those days were ancient history. Jews were well-established members of Cuban society. Most were middleclass merchants—a group with whom Batista had no problem. One of his closest associates was Meyer Lansky, a Jewish “businessman” he brought to Cuba to sanitize gambling operations after a high-profile 1953 article in the Saturday Evening Post singled out the island’s casinos for particular corruption. Most of Cuba’s twenty thousand Jews lived in Havana, a city that boasted Jewish schools, kosher restaurants, and three synagogues, the most well-attended being Beth Shalom (better known as El Patronato), a Conservative, meaning non-Orthodox, congregation. Construction had been funded by the most prosperous of Havana’s Jews, my grandfather Alberto among them.

In late 1956, when I was born, Cuba quivered with revolutionary fervor. Acts of sabotage, including bombs exploding in neighborhood trash cans, were commonplace. Students would be found shot dead by military police. “We were used to political violence,” my father said. “It was more or less the way regime change happened in Cuba.”

Two months after my mother came home from the maternity hospital, revolutionaries opened fire on the Montmartre nightclub, a nightspot a few blocks from our house that had featured performances by Lena Horne, Édith Piaf, and Cab Calloway. The chief of the island’s feared military intelligence service was killed in the attack, and the international press reported that bleeding women in evening gowns stumbled into bullet-riddled mirrors as they tried to flee the horror.

Then on New Year’s Eve, the busiest night for Havana’s nightclubs, a bomb detonated at the Tropicana. That one really shook my family. One of their neighbors in the building was a radio announcer who broadcast his shows from the glamorous open-air nightclub, and regularly invited my parents to sit at his ringside table. “We probably would have been there if you hadn’t just been born,” recalled my father.

Still, the warfare that mattered most to our family was in-house. My mother and grandfather were at it constantly. He, who had “saved a dime out of every dollar he made,” according to my father, criticized her spending. The whole family worked at the store on Calle Bernaza, the men arriving in the morning, and the woman coming only for the afternoon shift, after lunch and siesta. But while Abuela Blanca took the trolley from Vedado to Old Havana, my mother would wait around until the last minute, then treat herself to taxis. At home she had a cook and laundress. When I was born, a nanny came along. My grandmother did all her own cooking and housework.

“Your father wanted to give me everything I didn’t have,” my mother explained defiantly. This included renting a summer house in the beach town of Santa Maria del Mar, paying for her brother Felix’s schooling, and looking the other way as she filched cash from the register to buy furniture and clothes for her father, Ana, and Felix.

Poverty has a way of gouging out all sense of moderation. As a friend who was raised in abject circumstances explains: “If you’ve ever had to stare into an empty refrigerator, you will never again have one that is not packed full, even if you can’t possibly finish what’s inside.”

My mother was also egged on by her father, the perpetual gambler, with whom she’d made up right before her wedding. “I once took him with me to El Encanto to buy a bathing suit. My father had never been inside the store before. When I tried on the suit and asked what color he thought I should get, he said, ‘Get it in every color!’”

The clashes between my mother and paternal grandfather reached a breaking point just months before I was born. The store on Calle Bernaza was packed to the rafters with merchandise, some of which was on high shelves. One busy day, a customer came in, asking for a particular doll for his daughter’s birthday. Six months pregnant, my mother asked another employee to climb the steep ladder to bring a box down. My grandfather Alberto barked, “Get it yourself and don’t bother others with work you should be doing.” Whether that is what he said or what my mother heard is lost to history. She started up the ladder, then missed a rung and fell to the ground.

Rushed to the hospital, she was terrified of losing not only the baby, but her own life, given what had happened to her mother. She was confined to bed rest for the next three months. Alberto was contrite and despondent. “He came to visit me, white as a sheet,” recalled my mother. “He practically got onto his knees, begging for forgiveness. I told him: ‘If I lose this child, I’ll kill you. I’ll go to jail, but I will kill you. Count on it.’”

In conservation there’s a term for works of art that come with intrinsic defects: inherent vice. In paintings, such fabrication flaws appear when an artist uses impasto (the thick application of pigment to a painting) that is too heavy to be held by a canvas, or oil paint underneath acrylic, a condition that leads to cracking and flaking as the oil paint cures, releasing gases that get trapped beneath the plasticky acrylic. When bronzes leach the remnants of an inner mold, called the “investment,” through tiny pores or casting imperfections, that is inherent vice. So is the galvanic corrosion caused by welding two disparate metals together.

Items made of fired clay, such as ceramics, tiles, and terracotta, can display inherent vice in many ways. My friend and colleague Amy Green, a conservator and trained ceramist, explains: “Clays can have imperfections and inclusions. The firing temperature can be too low or too high. The temperature can be correct, but the item can be sitting in a cool spot in a kiln, or there can be an incompatible coefficient of expansion and contraction between the glaze and the clay, which can cause lifting or ‘shivering’ of the glaze, eventually having it fall off.”

A conservator can’t reverse such damage; she can only manage it.

Buy on Amazon | Bookshop.org

About the Author

Rosa Lowinger is a Cuban-born American art conservator and founder of RLA Conservation of Art + Architecture, LLC. (www.rlaconservation.com), the U.S.’s largest woman-owned materials conservation practice. She is also a published author, most well-known for Tropicana Nights: The Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub (Harcourt, 2005), a book on Havana’s pre-Castro nightclub era currently optioned for television by Keshet International, the company responsible for Homeland, Our Boys, and The Baker and the Beauty. Other fictional works by Rosa include The Encanto File, a play produced off-Broadway by the Women’s Project and Productions and published in Rowing to America and Sixteen Other Short Plays, edited by Julia Miles (Smith & Kraus, 2002), and The Empress of the Waves, a short story published in the anthology Island in the Light/Isla en la Luz (Trapublishing, 2019).

Rosa’s academic and professional distinctions include the 2008-09 Rome Prize at the American Academy in Rome, where she researched the history of vandalism, graffiti, and street art; and Fellow status in the American Institute for Conservation and the Association for Preservation Technology.

She holds an M.A. in Art History and Conservation from NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, lectures regularly at numerous universities around the country, and serves on the boards of the Amigos of the Cuban Heritage Collection at University of Miami, Florida Association of Museums, the Partnership for Sacred Places, and the Florida Association of Public Art Professionals.

Rosa co-curated the exhibits Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure American Seduction (Wolfsonian Museum, 2016) and Concrete Paradise: Miami Marine Stadium (Coral Gables Museum, 2013). She writes regularly for academic and popular media about conservation, the arts, and Cuba. Her 1999 cover story on Havana for Preservation spawned a career in cultural travel that has taken her to Cuba over 100 times since 1992.