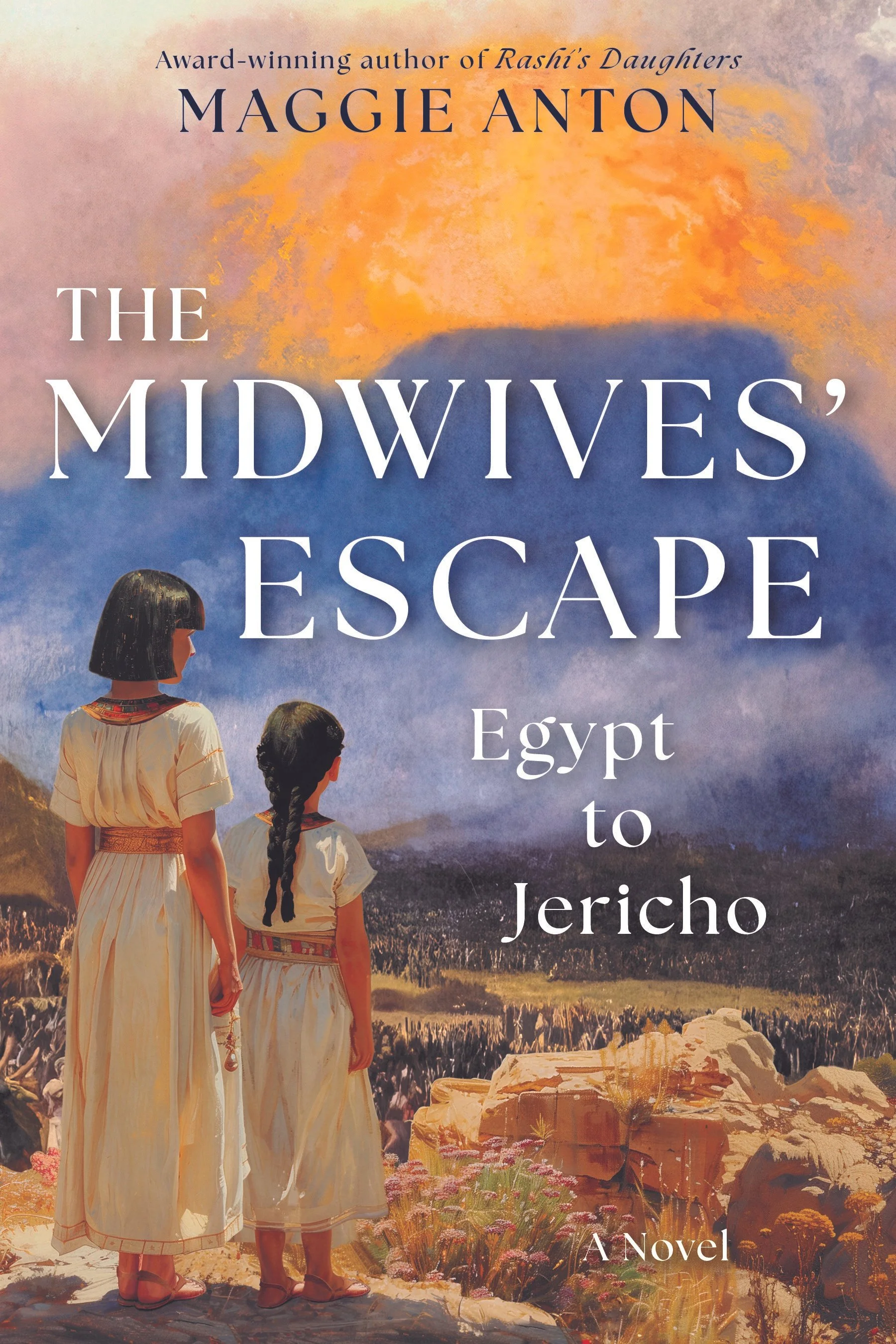

Spotlight: The Midwives' Escape: From Egypt to Jericho by Maggie Anton

/After years of archaeological research and biblical studies, award- winning author Maggie Anton has created a historical novel filled with adventure, warfare, and romance, true to both Torah and to history.

The Bible contains many extraordinary stories of a sometimes benevolent, sometimes vengeful deity, who guides the Israelites out of slavery, across the Sea of Reeds and through the wilderness to the Promised Land.

Maggie Anton's THE MIDWIVES ESCAPE: From Egypt to Jericho brings to life this exceptional Biblical journey through vivid descriptions of what daily life was like at this time, epic battlefield scenes and a colorful cast of characters.

An Egyptian mother and daughter, Asenet and Shifra, a midwife and her apprentice, wake up on the morning of the tenth plague to find Asenet's husband and son, both firstborns, dead. Asenet's sister Pua, married to an Israelite, urges Asenet's family to leave Egypt with them, which they reluctantly do, along with Asenet's wainwright father and his two apprentices. Recognizing that the Hebrew god is more powerful than any of the Egyptians' gods, other non-Israelites join the exodus, including Hittite and Nubian palace guards. Once hearing and accepting God's commandments at Mt. Sinai, these two Egyptian midwives join the Israelites on their forty-year journey to The Promised Land where they tend to the wounded, share hardship and adversity, fall in love, and start a new home and a new generation.

With THE MIDWIVES' ESCAPE, Anton has written an original and stunning recreation of the trials and tribulations on the road to the Promised Land.

Excerpt

Text copyright © 2025 by Maggie Anton, Published by Banton Press

Two weeks later, I got up from bed to discover blood running down my legs. I couldn’t find any wound and nothing hurt, so I ran excitedly to tell Mother. She’d obviously been expecting this because she brought me a sinar, something like a loincloth, stuffed with the same soft and absorbent kid’s wool swaddling that Tantana wore. “You are a woman now,” Mother whispered as she gave me a long hug. “So you will need to take care around men when they are in our family’s tents, because tradition limits contact between men and menstruating women.”

She hugged me tighter and I could see tears on her cheeks. “It is your responsibility to rinse the blood from your sinar with cold water, hang the wool in the sun to dry, and replace it with clean dry wool. You should also note the phase of the moon when your menses start, for that is when it will come each month.”

“But there is no moon out tonight,” I said.

“That’s because it was a new moon, the start of a new month, an auspicious time for beginnings,” she explained. “You will probably see a small crescent moon tonight.”

“What phase of the moon is it when your menses starts?”

She smiled. “I’m still nursing Tantana, so I don’t have any. When I start again, we’ll likely bleed at the same time since we live together.”

I’d gotten up to go put on the sinar and its swaddling, when she stopped me. “Wait,” she said. “I have something for you” Mother opened a box that Grandfather had made and removed two bronze anklets. “These anklets symbolize your transformation from girl to young woman; they mark you as marriageable in our community,” she said as she slid them over my feet. “Now we can plan your wedding to Eshkar.”

There was nothing else to do but go back to bed. But along with feelings of pride and excitement, there were now cramps in my belly. When I complained to Mother, she sighed and said that I’d probably have them every month until I married.

She must have shared the news with the rest of the family because the topic of conversation at our midday meal was how soon to announce my betrothal to Eshkar, after which we could start planning the wedding. Arrangements would be simplified because I wasn’t actually leaving home. True I would move out of the children’s tent and sleep with Eshkar in our own marital tent, but I wouldn’t require a dowry and he didn’t need to pay a bride price. Best of all, I wouldn’t be marrying a stranger.

There was one complication—something I must keep secret from anyone not in our immediate family. Grandfather explained it to me. “You know that the Hebrews, like most peoples, permit a man to marry two women; that is, to have two wives, as long as he can support both of them.” He waited until I nodded my understanding, then sighed. “Well, the Lagash custom is for a woman to marry two men—provided that they are brothers.”

My jaw dropped in astonishment as I looked from Eshkar to Gitlam and back again; then I quickly closed it. “So their father and uncle were actually both married to their mother?” Eshkar appeared unfazed, but Gitlam was blushing furiously.

“True,” Grandfather answered. “The elder is called ‘father’ and the younger ‘uncle,’ but either one could be the father of the mother’s children.”

“But why have such a custom?” I asked. I understood that in a place where armies regularly fought each other, women might outnumber men, like with the Hebrews and Hittites.

Eshkar replied, “The Lagash land was poor and infertile. If a father had many sons and wanted to divide his land equally among them when he died, none of them would inherit enough to support a family.”

Grandfather grinned. “Marrying brothers means the wife only has one mother-in-law.”

“Take as much time as you need to consider this,” Mother said.

There was nothing for me to consider. I’d understood for years that I would marry Eshkar. If he didn’t object to my also marrying Gitlam, I didn’t either. I liked them both well enough, and I would have several years to get used to the idea of having two husbands before Gitlam was old enough to marry me. I didn’t want to reject their Lagash customs, but I especially didn’t want to hurt either of their feelings.

So I told Mother, and the rest of my family, “I would be happy to marry Eshkar and Gitlam.” Then I gave Gitlam a smile. “Once Gitlam is a bit older, of course.”

Buy on Amazon

About the Author

Maggie Anton was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California, where she still resides. Raised in a secular, socialist household, she reached adulthood with little knowledge of her Jewish religion. All that changed when David Parkhurst, who was to become her husband, entered her life, and they both discovered Judaism as adults. That was the start of a lifetime of Jewish education, synagogue involvement, and ritual observance. This was in addition to raising their children, Emily and Ari, and working full-time as a clinical chemist for Kaiser Permanente for over 30 years.

In 1992 Anton joined a women's Talmud class taught by Rachel Adler, now a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. To her surprise, she fell in love with Talmud, a passion that has continued unabated for thirty years. Intrigued that the great Talmudic scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, Anton researched the family and decided to write novels about them. Thus, the award-winning trilogy, Rashi's Daughters, was born, to be followed by National Jewish Book Award finalist, Rav Hisda's Daughter: Apprentice and its sequel, Enchantress.

Still studying women and Talmud, Anton has lectured throughout North America and Israel about the history behind her novels. Her most recent effort is the Ben Franklin Award winner for Religion, Fifty Shades of Talmud: What the First Rabbis Had to Say about You-Know-What, a light-hearted look at our Sages's surprisingly progressive views on sexuality. For more information visit https://www.maggieanton.com/.