Spotlight: Act of Negligence by John Bishop MD

/Something unusual is going on with the dementia patients at Pleasant View Nursing Home.

Dr. Jim Bob Brady, Houston orthopedic surgeon and amateur sleuth, finds himself in the midst of a different type of medical mystery. His friend and colleague, Dr. James Morgenstern, refers him a series of dementia patients with orthopedic problems from Pleasant View Nursing Home. Each patient dies, irrespective of the treatment, a situation that Doc Brady is unaccustomed to.

Each death prompts an autopsy, performed by another Brady colleague, Dr. Jeff Clarke, who discovers unusual brain pathology in each patient. Some of the tissue samples show nerve regeneration, a finding unheard of in dementia patients.

Doc Brady, enraged by the loss of his patients and obsessively curious about the pathologic findings, begins to investigate the nursing home, as well as its owner and CEO, Dr. Theodore Frazier. This leads Brady and Clarke on an adventure to discover the happenings at Pleasant View-an adventure that sees them running for their lives.

Excerpted from Act of Negligence. Copyright © 2021 by John Bishop. All rights reserved. Published by Mantid Press.

BEATRICE ADAMS

Monday, May 15, 2000

“Morning, Mrs. Adams. I’m Dr. Brady.”

There was no response from the patient in Room 823 of University Hospital. She was crouched on the bed, in position to leap toward the end of the bed in the direction of yours truly. I could not determine her age, but she definitely appeared to be a wild woman. Her hair was a combination of gray and silver, long and uncombed and in total disarray. She had a deeply lined face, leathery, with no makeup. Her brown eyes were frantic, and her head moved constantly to the right and left. She was clad only in an untied hospital gown which dwarfed her small frame. My guess? She wasn’t over five feet tall.

“Ms. Adams? Dr. Morgenstern asked me to stop by and see about your knee?”

She did not move or speak; she just continued squatting there in the hospital bed, bouncing slightly on her haunches, and staring at me while her head moved slowly to and fro.

I looked around the drab private room with thin out-of-date drapes and faded green-tinted walls. There were no flowers. I judged the patient to most likely be a nursing-home transfer.

I made the safe move by backing out of the patient’s room, and I walked the twenty yards to the nurses’ station. The white-tiled floors were freshly waxed, but the medicinal smell was distinctly different from the surgical wing. There was an unpleasant pine scent in the air that could not hide the odor of decaying human beings and leaking body fluids. It was the smell of chronic illness and disease.

“Cynthia?” I asked the head nurse on the medical ward, or so announced her name tag. She was sitting at the far side of the long nursing station desk performing the primary duty of a nursing supervisor: paperwork. She was an attractive Black woman in her mid-forties, I estimated.

“Yes, sir?”

“Dr. Morgenstern asked me to see Mrs. Adams in consultation. Room 823? What’s the matter with her? She won’t answer me. She just stares, sitting up in the bed on her haunches, bouncing.”

She smiled and shook her head. “You must be a surgeon.”

“Yes, ma’am. Orthopedic. Dr. Jim Brady.”

“Cynthia Dumond. Mrs. Adams has Alzheimer’s. Sometimes she gets confused. Want me to come in the room with you? Maybe protect you?” she said with a smile.

“Well, I wouldn’t mind the company,” I said, a little sheepishly. “Not that I was afraid or anything.”

“She’s harmless, Doctor. She’s just old and confused.”

We walked back to the hospital room together. The patient seemed to relax the moment she saw the head nurse, a familiar face. “Hello, Ms. Adams,”

Cynthia said. “This is Dr. Brady. He needs to examine your . . .” She gazed at me, smiling again. “Your what?” “Her knee.”

“Dr. Brady needs to look at your knee. Okay?”

The patient had ceased shaking and bouncing, leaned back, slowly extended her legs, laid down, and became somewhat still.

“Very good, Ms. Adams. Very good,” Cynthia said, grasping the elderly woman’s hand and holding it while she looked at me. “Go ahead, Doctor.”

The woman’s right knee was quite swollen, with redness extending up and down her leg for about six inches in each direction. When I applied anything but gentle skin pressure, her leg seemed to spasm involuntarily. How in the world she had managed to crouch on the bed with her knee bent to that degree was mystifying.

“Sorry, Ms. Adams,” I said, but continued my exam. The knee looked and felt infected, but those signs could also have represented a fracture or an acute arthritic inflammation such as gout, pseudo-gout, or rheumatoid arthritis, not to mention an array of exotic diseases. I tried to flex and extend the knee, but she resisted, either due to pain—although I wasn’t certain she had a normal discomfort threshold—or from a mechanical block due to swelling or some type of joint pathology.

“What’s she in the hospital for?” I asked Nurse Cynthia.

“Dehydration, malnutrition, and failure to thrive, the usual diagnoses for folks we get from the nursing home. The doctor who runs her particular facility sent her in.”

“Who is it?”

“Dr. Frazier. Know him?”

“Nope. Should I?”

“No. It’s just that he sends his patients here in the end stages. Most of the folks that get admitted from his nursing home die soon after they arrive.”

“Most of them are old and sick, aren’t they?”

“Yes.”

I looked at her expression while she continued to hold Mrs. Adams’s hand.

“Were you trying to make a point?”

“Not really.” She glanced at her watch. “Are you about through, Doctor Brady? I have quite a bit of work to do.”

“Follow that paper trail, huh?”

“Yes. That’s about all I have time for these days. Seems to get worse every month. Some new form to fill out, some new administrative directive to analyze. Whatever.”

“I know the feeling. There isn’t much time to see the patients and take care of whatever ails them these days. If my secretary can’t justify to an insurance clerk why a patient needs an operation, then I have to waste my time on the phone explaining a revision hip replacement to someone without adequate training or experience. One of my partners told me yesterday about an insurance clerk that was giving him a bunch of—well, giving him a hard time—about performing a bunionectomy. He found out during the course of a fifteen-minute conversation that the woman didn’t know a bunion was on the foot. Her insurance code indicated it was a cyst on the back and she couldn’t find the criteria for removal in the hospital. She was insisting it had to be an office procedure, and only under a local anesthetic. Crazy, huh?”

“Yes, sir. It’s a brave new world.”

“Sounds like a good book title, Nurse Cynthia.”

“I think it’s been done, Doctor.”

“Well, thanks for your help. I do appreciate it. Not every day the head nurse on a medical floor accompanies me on a consultation.” “My pleasure. You seem to be a concerned physician, an advocate for the patient, at least. As I remember, that’s why we all went into the healing arts.”

She turned to Mrs. Adams. “I’ll see you later, dear,” she said, patting the elderly woman’s forehead. Still holding the nurse’s other hand with her own wrinkled hand, Mrs. Adams kissed Cynthia’s fingers lightly, probably holding on for her life.

I poured a cup of hospital-fresh coffee, also known as crankcase oil, and reviewed Beatrice Adams’s chart. I sat in a doctor’s dictation area behind the nursing station and looked at the face sheet first, being a curious sort. Her residence was listed as Pleasant View Nursing Home, Conroe, Texas. Conroe is a community of fifty thousand or so, about an hour north of Houston. I noticed that a Kenneth Adams was listed as next of kin and was to be notified in case of emergency. His phone number was prefixed by a “409” exchange, and I therefore assumed that he was a son or a brother and lived in Conroe as well.

Mrs. Adams was fifty-seven years old, which was young to have a flagrant case of Alzheimer’s disease, a commonly-diagnosed malady that was due to atrophy of the brain’s cortical matter. That’s the tissue that allows one to recognize friends and relatives, to know the difference between going to the bathroom in the toilet versus in your underwear, and to know when it’s appropriate to wear clothes and when it isn’t. Alzheimer’s causes a patient to gradually become a mental vegetable but doesn’t affect the vital organs until the very end stages of the disease. In other words, the disease doesn’t kill you quickly, but it makes you worse than a small child—unfortunately, a very large and unruly child.

It can, and often does, destroy the family unit, sons and daughters especially, who are caught between their own children and whichever parent is affected with the disease, which makes it in some ways worse than death. You can get over death, through grief, prayer, catharsis, and tincture of time. Taking care of an Alzheimer’s-affected parent can be a living hell, until they are bad enough that the patient must go to a nursing home. Then the abandonment guilt is hell, or so my friends and patients tell me.

Mrs. Adams had been admitted to University Hospital one week before by my friend and personal physician, Dr. James Morgenstern. I guessed that either he had taken care of the patient or a family member in the past, or that Dr. Frazier, physician-owner or medical director of Pleasant View Nursing Home, had a referral relationship with Jimmy.

Mrs. Adams’s initial blood work revealed hyponatremia (low sodium), hyperkalemia (high potassium), and a low hematocrit (anemia). Clinically, hypotension (low blood pressure), decreased skin turgor, and oliguria (reduced urine output) suggested a dehydration-like syndrome. For a nursing-home patient, that could either mean poor custodial care or failure of the patient to cooperate— refusing to drink, refusing to eat—or some combination of the two. Neither scenario was atypical of the plight of the elderly with a dementia-like illness.

According to Dr. Morgenstern’s history, the patient had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease six years before, at age fifty-one, which by most standards was very young for brain deterioration without a tumor.

“Dr. Brady?” head nurse Cynthia asked, appearing beside my less-than-comfortable dictating chair.

“Yes?”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but might I have one of your business cards?”

“Sure,” I said, handing her one from the top left pocket of my white clinical jacket. “Don’t ever apologize for bothering me if you’re trying to send me a patient.”

She laughed. “It’s for my mother. She has terrible arthritis.” She paused and read the card. “You’re with the University Orthopedic Group?”

“Yes. Twenty-two years.”

“If I might ask, where did you do your training?”

“I went to med school at Baylor, then did general and orthopedic surgery training here at the University Hospital. I then traveled to New York and spent a year studying hip and knee replacement surgery, then came back to Houston to the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

“Is your practice limited to a certain area? I mean, do you just see patients with hip and knee arthritis?”

“Yes. Unless, of course, it’s an emergency situation, like one of those rare weekends when I can’t find a young, hungry surgeon with six kids to cover emergency room call for me.”

“Well, thanks,” she said, smiling. “I’ll be seeing you. I’ll bring my mother in.”

“Thank YOU, Cynthia. By the way, I’m curious. Why me? I would think you see quite a few docs up here, and I would imagine that your mother has had arthritis for years. Why now?”

Cynthia was an attractive, full-figured woman with close-cropped jet-black hair, a woman who made the required pantsuit nursing uniform look like a fashion statement. She looked me up and down as I sat there with Mrs. Adams’s chart in my lap, my legs crossed, holding the strong black cooling coffee.

“You’re wearing cowboy boots. I figure that all you need is a white hat,” she said, turning and walking away.

Not my sharp wit, nor my kind demeanor with her patient, nor my vast training and experience.

My boots.

Buy on Amazon Kindle | Paperback

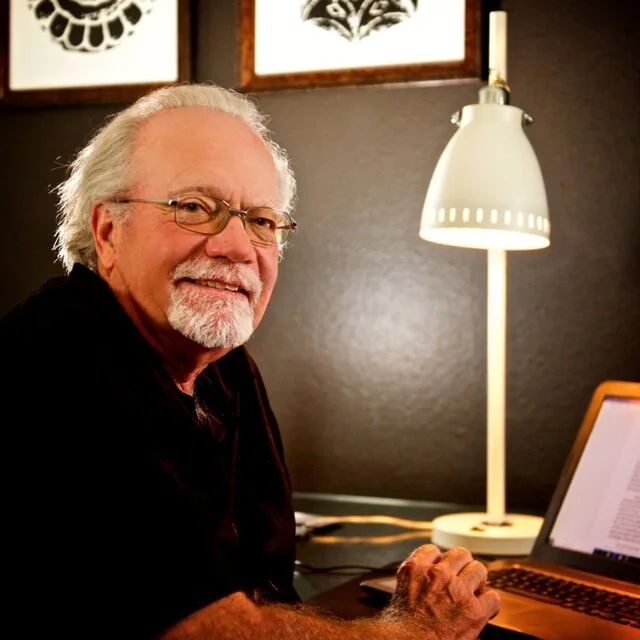

About the Author:

John Bishop MD is the author of Act of Negligence: A Medical Thriller (A Doc Brady Mystery). Dr. Bishop has led a triple life. This orthopedic surgeon and keyboard musician has combined two of his talents into a third, as the author of the beloved Doc Brady mystery series. Beyond applying his medical expertise at a relatable and comprehensible level, Dr. Bishop, through his fictional counterpart Doc Brady, also infuses his books with his love of not only Houston and Galveston, Texas, but especially with his love for his adored wife. Bishop’s talented Doc Brady is confident yet humble; brilliant, yet a genuinely nice and funny guy who happens to have a knack for solving medical mysteries. Above all, he is the doctor who will cure you of your blues and boredom. Step into his world with the first four books of the series, and you’ll be clamoring for more. For more information, please visit https://johnbishopauthor.com