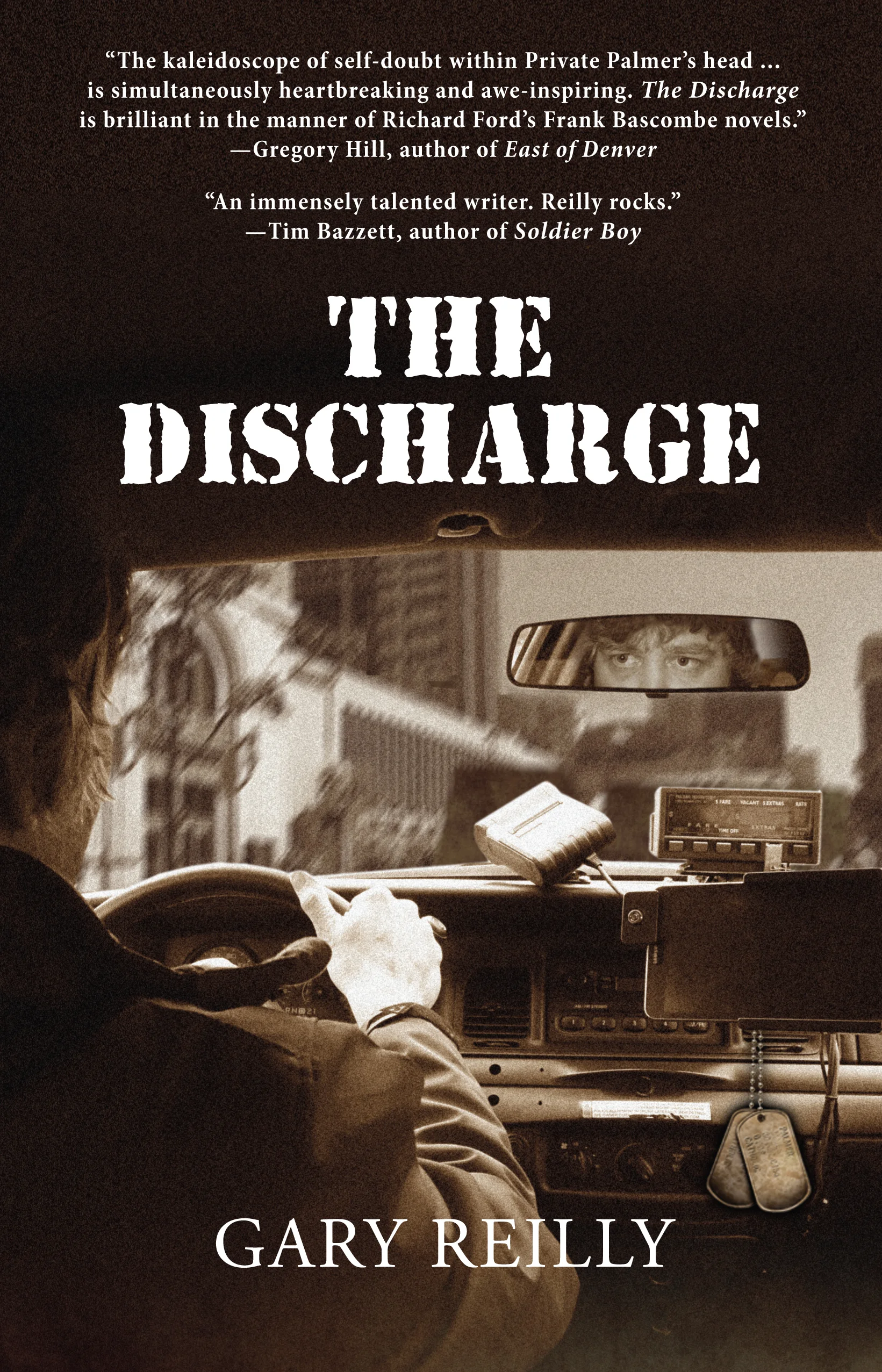

Read an excerpt from The Discharge by Gary Reilly

/The Discharge is the third novel in Gary Reilly’s trilogy chronicling the life and times of Private Palmer as he returns from the U.S. Army to civilian life after a tour of duty in Vietnam. It is a largely autobiographical series based on his own two years of service, 1969-1971, which included a year in Southeast Asia.

In the first book, The Enlisted Men’s Club, Palmer is stationed as an MP trainee at the Presidio in San Francisco, awaiting deployment orders. Palmer is wracked with doubt and anxiety. A tortured relationship with a young lady off base and cheap beer at the EM club offer escape and temporary relief.

The Detachment is the second in the series. This novel covers Palmer’s twelve months in Vietnam as a Military Policeman. In the beginning, he endures through drink and drugs and prostitutes but comes to a turning point when he faces his challenges fully sober.

Now, in The Discharge, Palmer is back in the United States. But he’s adrift. Palmer tries to reconnect with a changed world. From San Francisco to Hollywood to Denver and, finally, behind the wheel of a taxi, Palmer seeks to find his place.

Excerpt

From Part 3: Winter

1

Now that he had a source of income, Palmer decided it was time he moved out of his basement apartment. He had lived there for a year after he had broken up with his last girlfriend, and it was the place where he had endured the worst of the bad dreams of his life. They were not the frightening dreams of childhood, of arms reaching out of the darkness to grab an ankle, they were dreams of anguish, contrasted with dreams of peculiar joy. He had rarely dreamed about Vietnam after he'd come home from the war, yet during the past six months he had begun having dreams where he found himself back on the army compound where he had served as a clerk/typist.

The architecture of the compound was a bit different, in the way that most familiar places are skewed in dreams, but was enough like his old duty station that he knew where he was and what was expected of him, that he would be required to spend another year in Vietnam. He stormed angrily around the compound in these dreams, exasperated that he had to do it all over again, that he had to re-experience that oppressive sense of dread that had enveloped him like a suffocating blanket during his tour twenty years ago. But oddly enough he never sought out a battalion clerk or an officer in these dreams, to explain that he had already served his year and that he was under no legal obligation to do it again. He simply accepted it as he had once accepted his real tour. He would awaken from these dreams drained from frustration, yet not especially relieved to be awake.

One night he dreamed that he was dead. The cemetery where his body was interred, the landscape itself, was made of stone. There were no lawns, no acres of empty space, only tombs rising no more than waist high and crowded together like a city which stretched into the dream distance. His tomb was right next to a large motionless body of water which extended in the opposite direction, describing a curved horizon. This tombscape was engraved with random, meandering, narrow paths, so that the living could walk among the graves. The low walls of these paths had embossed carvings of skulls, bones, and random intricate interlocking designs. He himself was dead, was a ghost floating above his tomb in a pleasant state of mind that was almost physical in its intensity, was unlike anything he had ever experienced in waking life. He drifted here and there among the tombstones, and was aware of one other ghostly presence but felt no fear or even any particular need to communicate with it. Living visitors were walking among the tombstones, families of the deceased. He felt no compulsion to draw close to them, to listen in on their conversations. He felt no particular need to do anything at all. Far across the body of water was the glow of what he thought must be a city. He neither knew nor cared, and when he awoke from this most peculiar of dreams, he kept his eyes closed and clung to its sweet ambiance as long as he could.

Whenever he dropped a passenger off in an unfamiliar neighborhood, Palmer took note of any For Rent signs he might see planted behind window glass. He would study the house or apartment building and try to imagine himself living there. He wanted some place where he could stay for a long time, a place from which he would not feel the need to flee for at least a year. He did not want to live in the suburbs, nor on Capitol Hill which had been taken over by punk rockers in the way that the heart of the city had been overrun by hippies when he had been a teenager. And he did not want to live so far away from the cab company that he would find it complicated to get there if his heap ever broke down and he had to take a bus. He did not know where he wanted to live, only that he had to get out of that awful basement apartment as soon as possible. He had the money now. This job seemed to be working.

It had not worked very well the first few shifts. He had made all the mistakes that Pemberton had warned him about, and had invented a few of his own. One day he failed to tighten the radiator cap after checking the water level, so that the water evaporated, the engine overheated and seized up, and the cab had to be towed back to the company at a cost of twenty-five dollars to Palmer, upon whom the mechanics placed the blame after discovering the loose radiator cap.

On another day he picked up a man at a bar, and then made the mistake of letting the man go into an apartment complex unescorted to "get the money." The man never came out.

On his first day of driving Palmer had earned a total of five dollars, even though he worked the maximum twelve hours. His very first fare from the airport was a cowboy who had left his truck over the weekend in the parking lot of a girls' school a few blocks from Stapleton, so that the fare was not fifteen dollars as Palmer had expected for his first trip ever out of the airport, but three dollars.

He quickly drove back to the airport and pulled up in the cab line, but not so quickly that he could outrace the sense of futility that had begun to overwhelm him. From the very outset of cab driving, from the get-go, things were not working out the way he had hoped. He was old enough to know that there was no justice in the universe, but it seemed that the odds ought to occasionally go his way through sheer caprice.

He came home that night with a fleeting sense of horror that this job was not only not going to work, it could not even be considered real. Where was that wad of long green which had made an obscene bulge in Pemberton's breast pocket? But then how many times in his life had he discovered that there was more to learning than watching someone else do it. Imitation. That word had subtle meanings that he had never appreciated until he tried doing things. Fake. Fraud. Authenticity was like a missing ingredient that he could never quite corner, capture, put to any use. If cab driving didn't work out, then he didn't know what he was going to do. But there was nothing to do except keep on trying, because the alternatives, of which there were many, were unthinkable. He had to make this work, and before winter came, he did.

On the day of the first snowfall of the season, Palmer was netting an average of sixty dollars a shift for twelve hours of driving, the same pay scale most teenagers got for flipping burgers, minus the supervision of a cranky manager, a foreman, a boss. He had enough money in the bank to begin looking in earnest for a new place to live, first and last month's rent, cleaning deposit, all the crap of paranoid landlords, although he did not realistically expect to live in a place where such things were a major concern to the live-in managers who collected rent for absentee owners. He in fact expected to live in the neighborhood of the punks and the college students going to school nights and working shit jobs in the daytime. He expected to end up on Capitol Hill.

Whenever he drove through that part of town and saw the young people in their tattered blue jeans and rock haircuts and drug jackets, he was reminded that he was forty-two years old and would not fit in, that to these young minds the Beatles were as obsolete as Tommy Dorsey had been to his own generation. Still, he contemplated the For Rent signs in the grimy windows of the buildings in that part of town as if he were looking for a room that resembled his youth.

The first snowfall was light, left only a dust of white powder on the streets, did not stick and was blown aside by the tires of passing cars. A niggling fear sprouted in Palmer's gut at this first sign of what might turn out to be an obstacle to his success. How many times in the past had he seen only cabs moving along the streets in heavy snowstorms? Up to now he had always arranged his life so that when the snow arrived and the parked cars at curbs began resembling the skyline of the Rockies he would never have to leave his apartment. Fifteen years earlier he had been fired from a job he didn't like. It primarily involved delivering carpets. Like giant redwoods those carpets were, rubber-backed and woven of artificial fibers, they made his legs bow when he and the driver trundled up sidewalks and entered the homes of pleased women who fretted as he let the monstrous weight drop on hardwood floors. It was like carrying a sofa bed on one shoulder. He did not go to work because he imagined himself slipping on an icy sidewalk, breaking a leg, a pelvis, manufacturing a hernia, all for a dollar above the minimum wage. His girlfriend had answered the phone when it rang that morning and said Palmer was too sick to come to work. His boss told her to tell Palmer not to bother coming back at all. Palmer was thirty-two years old, and the world was filled with pissed bosses.

One morning after dropping off a fare on Capitol Hill, Palmer drove past a For Rent sign planted discreetly on the large front porch of a three-story apartment building. The placard was black, the letters bright red, a sign you'd buy in a hardware store or a Woolworths. The sign caught his eye only because he became attuned to spotting obscure signs after he had begun what was turning into a rather desultory search.

The apartment was in a neighborhood which was old but not run-down. People in their late twenties and early thirties would live here, residents who held mid-level jobs—clerks, nurses, shipping-and-receiving. He backed the cab up quickly with the renegade attitude of freedom from rules that comes from driving a cab, and parked at the curb in front of the building.

Unlike the other buildings nearby with their flat tar-topped roofs, this one had a gabled roof plastered with green shingles, with one window looking out from what he assumed was an attic. The second floor had a pair of French doors that opened onto a massive stone balcony which hid the front door of the first floor in shadow. He got out and approached the sign, looked for the rent price which was sometimes scribbled in pencil on these cheap advertisements, but there was nothing to indicate how much it would cost him to live in this place which he felt drawn to. He knew the history of these places, knew that they had been the homes of wealthy families during the nineteenth century, the buildings gone to seed in a modern world, broken up into small apartments with jury-rigged bathrooms and kitchens the size of closets. He went up to the front door and looked at a row of doorbells molded in brass. He punched the bell adjacent to the word "Manager" inscribed in blue plastic tape.

He heard footsteps approaching on a carpeted hall floor, imagined a sprightly matron, or a man who had retired from the military and was supplementing his pension with this kind of work, but was surprised when a kid who could not have been more than twenty opened the door. Fringe of dark brown beard on his chin, dark bright eyes, he was wearing a T-shirt and cut-off jeans, tennis shoes, looked like a college student. Palmer was so surprised at encountering someone who was not old that he felt as if he were speaking to an equal and not someone twenty-two years younger than himself.

"I saw your for-rent sign," Palmer said. "Is the apartment still available?"

"I was just heading out for a class at the free university but I could show you the place real quick," the kid said. He had a rapid, chortling voice, and fingered his chin as he spoke. He led Palmer up a staircase that grew narrower as it rose higher. Up to the second floor and then up another staircase that was even tighter, and which took a right turn near the top. Three more steps and there was a door flush against a wall. Palmer tried to imagine how a sofa bed might be delivered to this apartment. The manager produced a chain of keys, opened the door, led him inside.

The layout of most apartments could be grasped in an instant, so whenever Palmer walked in he knew where everything was and whether or not he liked it. But when he entered this place he found himself in a small foyer with doorways leading off in different directions. The manager opened one door and said something about it being a storage room, although it was carpeted and had a window which let in strong light. The room looked as if it could serve as a nursery. They moved into the living room, which was high ceilinged and wide. This took them to the kitchen, and then into the bathroom with a tub, no shower, and Palmer began to get the sense that the place was sprawling. The small kitchen had six windows, had a door which led to the outside. The manager explained that the kitchen had been added on years ago. It was a kind of box.

Palmer went to a window and looked down. The room extended out over a dirt parking lot below. A steep fire-escape led from the door down to the scatter of parked cars owned by other tenants.

"Let me show you the bedroom," the manager said, and Palmer followed him back through the living room and into a long room facing the street, a narrow room with a low ceiling shaped like an A-frame. It was the attic he had seen from outside. There was a non-functioning fireplace in this space, was a small alcove off to the side with a desk in it, and another alcove where a shelf of books might be set up.

"How much is the rent?" Palmer asked only because he had to, because he was dazzled by this aerie, and knew from past experience that the price would be too high.

"Two-forty a month," the young man replied, the chortle disappearing now that they were discussing financial matters. "I know that sounds cheap, but the thing is, the owners want steady renters who are gonna stick around for a long time. They don't want someone who's just gonna throw a mattress on the floor and eat out of tin cans. If you're interested in renting the place, they'll want to know about your background and what kind of work you do and all that."

He didn't seem to be trying to discourage Palmer. Palmer sensed that the kid did not dislike him, that his being a tenant would be acceptable to this manager whose job it was to pass first judgment on the strangers who came to his door, an occupation similar to being a cab driver, but with its own unique intensities.

"I can bring you a deposit later today," Palmer said. "I can bring cash if you want."

"That would be good," the kid said, the chortle returning to his voice. "Cash up front always makes a good impression on the owner."

When Palmer got back into his cab he felt an excitement and a craving he had not known in years. He wanted that apartment, could not imagine anything as great as living in that crow's nest in the sky. He went to get the deposit money out of his bank, and as he drove, half-listening to the calls being offered on the radio, he considered just what he would write in the one-page resume about himself that the manager had suggested he produce as soon as possible.

"I left home at the age of eighteen," he said aloud to the voice of the dispatcher flowing ceaselessly out of the speaker, "and got a job delivering furniture. I was eventually drafted into the army. I served one year in Vietnam and returned home where I entered college on the GI Bill. I earned a Bachelor of Arts Degree in English. After that I held a variety of jobs . . ."

This first part was easy to voice impromptu because it had the quality of a short story in which there is only so much room to describe what happened but very little space for in-depth explanations, whys, wherefores, justifications, apologies, excuses. When he got as far as leaving the drunken Eden of academia and taking his place in the real world, the mental pen with which he wrote all first drafts faltered. Most of the jobs he had held had been meaningless shit, and a few were actually painful to remember. There seemed nothing he had done since college worth mentioning in a resume, and as he approached the bank he realized that the biographical information he was obliged to write for the owner of the apartment building might end up taking the shape—like the taxi cemetery behind the cab company—of a motley collection of rather badly dented truths.

Buy on Amazon | Barnes and Noble

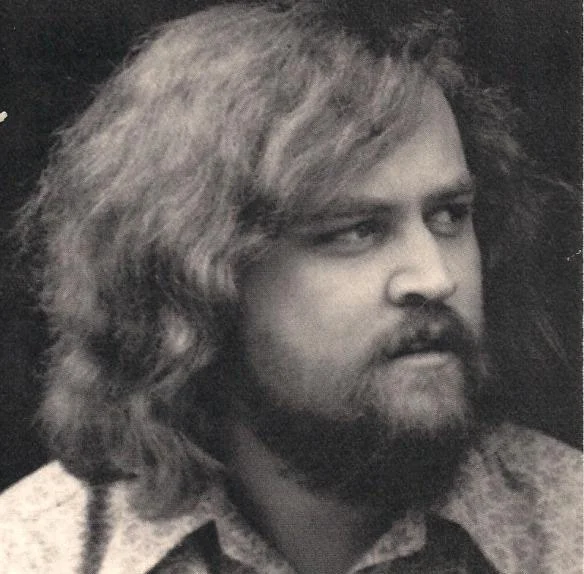

About Gary Reilly

Gary Reilly was a natural and prolific writer. But he lacked the self-promotion gene. His efforts to publish his work were sporadic and perfunctory, at best. When he died in 2011, he left behind upwards of 25 unpublished novels, the Vietnam trilogy being among the first he had written.

Running Meter Press, founded by two of his close friends, has made a mission of bringing Gary’s work to print. So far, besides this trilogy, RMP has published eight of ten novels in his Asphalt Warrior series. These are the comic tales of a Denver cab driver named Murph, a bohemian philosopher and aficionado of “Gilligan’s Island” whose primary mantra is: “Never get involved in lives of my passengers.” But, of course, he does exactly that.

Three of the titles in The Asphalt Warrior series were finalists for the Colorado Book Award. Two years in a row, Gary’s novels were featured as the best fiction of the year on NPR’s Saturday Morning Edition with Scott Simon. And Gary’s second Vietnam novel, The Detachment, drew high praise from such fine writers as Ron Carlson, Stewart O’Nan, and John Mort. A book reviewer for Vietnam Veterans of America, David Willson, raved about it, too.

There is a fascinating overlap in the serious story of Private Palmer’s return to Denver and the quixotic meanderings of Murph. It is the taxicab. One picks up where the other leaves off. Readers familiar with The Asphalt Warrior series will find a satisfying transition in the final chapters of The Discharge.

And they will better know Gary Reilly the writer and Gary Reilly the man.