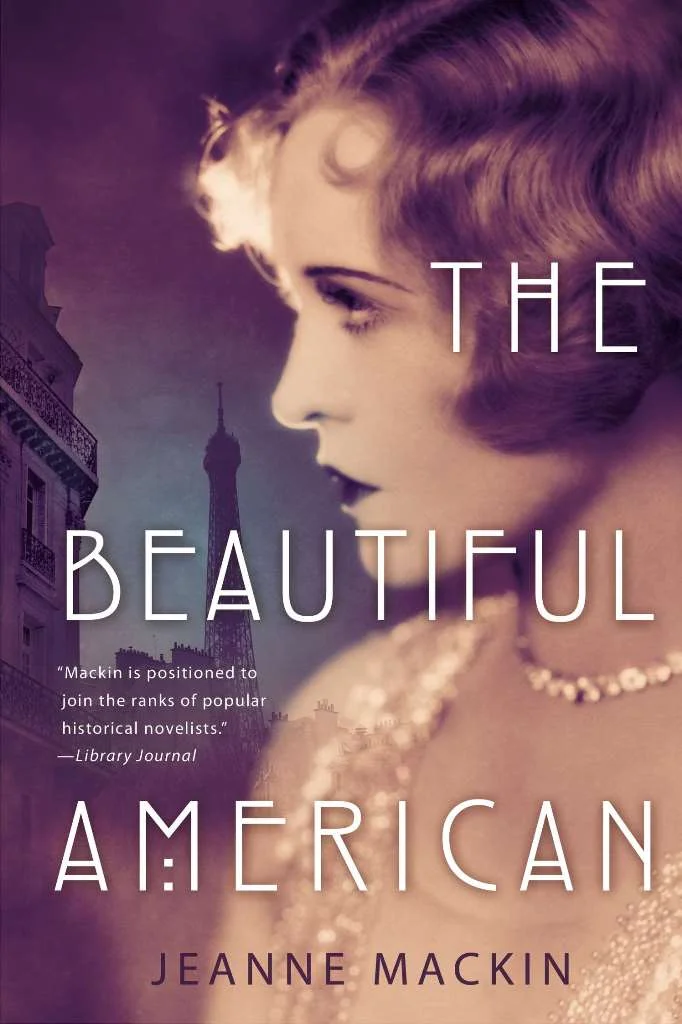

Read an excerpt from The Beautiful American by Jeanne Mackin

/As recovery from World War II begins, expat American Nora Tours travels from her home in southern France to London in search of her missing sixteen-year-old daughter. There, she unexpectedly meets up with an old acquaintance, famous model-turned-photographer Lee Miller. Neither has emerged from the war unscathed. Nora is racked with the fear that her efforts to survive under the Vichy regime may have cost her daughter’s life. Lee suffers from what she witnessed as a war correspondent photographing the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps.

Nora and Lee knew each other in the heady days of late 1920’s Paris, when Nora was giddy with love for her childhood sweetheart, Lee became the celebrated mistress of the artist Man Ray, and Lee’s magnetic beauty drew them all into the glamorous lives of famous artists and their wealthy patrons. But Lee fails to realize that her friendship with Nora is even older, that it goes back to their days as children in Poughkeepsie, New York, when a devastating trauma marked Lee forever. Will Nora’s reunion with Lee give them a chance to forgive past betrayals, and break years of silence?

A novel of freedom and frailty, desire and daring, The Beautiful American portrays the extraordinary relationship between two passionate, unconventional woman.

Excerpt

Prologue

Départ

The very first hint of fragrance, experienced when the perfume bottle is first opened, before the fragrance is in direct contact with the skin, the nose and the heart. Similar, really, to a book opened but not yet read...or, perhaps, a door opened to a visitor not yet visible, one who lurks in shadow. The départ begins the journey of the perfume and its wearer.

---From the notebooks of N. Tours

In the ornate doorway of Harrods perfume hall people rushed past me as I stood, frozen.

A radio played somewhere, Churchill's voice rising over the crowd, commending the English again for surviving the storm-beaten voyage. The war was over, we were picking up the pieces and carefully, slowly putting our lives back together. But my daughter was lost. The grief struck me anew and I was immobile in a doorway, unable to go forwards or backwards, unmoored by grief.

A summer afternoon long ago Jamie and I went to Upton Lake to swim and make love, and there had been a boat, abandoned by rich summer people who didn't know how to tie a knot, and the boat had bobbed in the waves, turning this way and that as a storm stalked over the lake. I was that boat. "Move on!" the doorman shouted at me, but my legs wouldn't work. I was exhausted. When I walked there was a chant in my head, Dahlia is gone, Dahlia is gone, over and over, a syllable with every step, so that I hated to move. People pushed past me, some smiling in sympathy, some merely irritated. Their string shopping bags and brown-wrapped boxes jostled me; their elbows poked.

The doorman frowned. He took me by the arm and pulled me out of that flood of people. "Look, dearie," he said. "Are you coming or going?"

"I don't know," I admitted.

His expression softened. He was an older man with a deeply lined face, pale eyes sunk into their sockets, and there was an authority to him that went beyond his doorman's uniform. Probably during the war he had been an air raid warden. He would have been too old to be a soldier.

"Well then," he said. "Why don't you go in? That's always a good starting point. There you go." He turned me around, gently, and gave me a little push, back to that threshold, where I suddenly remembered I wanted to enter, to continue the search for my daughter.

I moved through the doorway, overwhelmed by the synthetic florals and citruses of the post-war perfumes. They enter the nose aggressively, fighting for attention like unruly school children. What I most remembered about my own child was how the long braid she wore down her back smelled of lavender, a single note of innocence. My lost child.

Sixteen years ago, I ran away. And now, my daughter had, too, or at least I hoped she had, for the other possibilities were unthinkable. But after months of searching, I hadn't found Dahlia in any of those places where a young girl might find shelter: not in the homes of friends in southern France; not in Paris in the narrow streets of Montparnasse, the cafés and gardens and boulevards of those years with Jamie; not in the orphanages that sheltered children whose parents had not survived. She had left no trace.

So I had come, finally, to London, to the almost-beginning. Beginnings are like endings, never completely finished, simply receding like the horizon. Here, in the doorway of Harrods, one rainy morning almost two decades ago, Jamie and I had agreed that we would leave England and go to Paris, and that if all went well, we would marry and begin our family. I had told Dahlia that story, how I had dreamed of her years before she was born.

I had already been in London for three days, walking the streets, asking hotel clerks and checking registers at shelters, looking for her, fighting down panic and dread. The boarding house where Jamie and I had stayed had been bombed and so had the little pub where we had had our noon fish and chips and pint. There was destruction everywhere. St. Paul's Cathedral had been bombed, St. James Palace, Houses of Parliament. Half the population of London had been made homeless. This was no place for a young girl on her own, even one with papers and a little cash, for her papers and her savings had disappeared with her.

Dahlia is sixteen, I kept reminding myself. She was tall and strong and sensible. She spoke French and English fluently and could get by in Italian and German. She had good common sense. She had what she needed to survive, if her luck held.

How had I produced such a child, me, the gardener's daughter from Poughkeepsie? Dahlia was a wonder to me, but in my dread I didn't think of her as strong and competent, but as a lost child crying for her mother.

My lost child. Would I be returning home without her again? I had gone back and forth from Paris to Grasse for months, always leaving home with hope, returning in despair. Home again, without Dahlia. The thought kept me motionless inside that doorway.

"Hey!" a voice muttered. "Move on." A woman, tall, burdened with an armful of parcels, almost knocked me over in her haste to get out the door.

"Watch yourself!" I snapped back. The woman looked at me over the top of her packages.

"Oh my God," she said.

Once she had lowered her arms and I could see her face, I knew her immediately. Lee Miller.

The very famous and beautiful Lee Miller, the Vogue model, the muse for the artist Man Ray who had made of her lips an iconic image of a woman's mouth floating in the sky. She had gone on to become a famous photographer -- the only woman photographer who covered battles, not just field hospital follow-ups and stories about the war nurses. She had photographed the London Blitz, the siege of St. Malo, the Alsace Campaign, the camps in Germany. Nightmare photos.

Lee was heavier than I remembered, and there was a puffiness around the eyes and in the cheeks that drinkers sometimes got. But nothing, not war, alcoholism or middle age, could mar that perfect nose and those cheek bones, the thick wavy blonde hair now worn post-war style, falling over one eye. Those oh-so-famous lips.

We stood for a long while, staring at each other in disbelief. It’s not often that you run smack into your own past.

Buy on Amazon Kindle | Audible | Paperback

About the Author

Jeanne Mackin’s novel, The Beautiful American (New American Library), based on the life of photographer and war correspondent Lee Miller, received the 2014 CNY award for fiction. Her other novels include A Lady of Good Family, about gilded age personality Beatrix Farrand, The Sweet By and By, about nineteenth century spiritualist Maggie Fox, Dreams of Empire set in Napoleonic Egypt, The Queen’s War, about Eleanor of Aquitaine, and The Frenchwoman, set in revolutionary France and the Pennsylvania wilderness.

Jeanne Mackin is also the author of the Cornell Book of Herbs and Edible Flowers (Cornell University publications) and co-editor of The Book of Love (W.W. Norton.) She was the recipient of a creative writing fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society and a keynote speaker for The Dickens Fellowship. Her work in journalism won awards from the Council for the Advancement and Support of Education, in Washington, D.C. She has taught or conducted workshops in Pennsylvania, Hawaii and at Goddard College in Vermont.