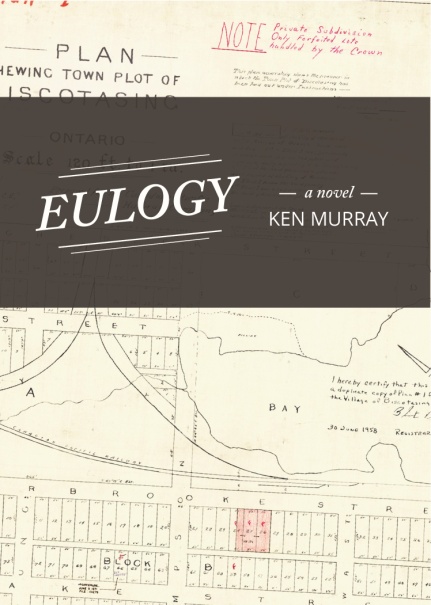

Read an excerpt from Eulogy by Ken Murray

/The controlled and calm life of William Oaks is shattered when his parents die suddenly in a car crash. A reclusive paper conservator at a renowned Toronto museum, William must face the obsessions and denials that have formed him: delusional family history, religious fundamentalism, living with unhappy parents who are constantly bickering, forced starvation, secrets and get-rich-quick schemes. Memory and facts collide, threatening to derail his life and career as William feverishly prepares for an important exhibition on the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Excerpt

One:

Toronto, December 2000—I visited my parents a few weeks before Christmas. Mom had left many messages, “William, where are you?” “William, are you okay?” “William, do you need any more Slender Nation?” I’d been ignoring her calls for months.

Terry had become a big part of my life, and I was happy. For the first time, I didn’t want to be alone. I had my work at the Royal Ontario Museum, and she had hers in one of the bank towers downtown, and we had each other, and we had our music, and we fell into that inner space that people find when they love someone. Terry burned brightly in my world, and the rest of the world faded. Work was still good, but I fell out of touch with home, and for good reason; I didn’t want to tell my parents about her because I didn’t want to deal with their questions. I stopped calling, stopped visiting.

But dealing with it became inevitable: I had to tell my parents that I had a girlfriend, and even though I was a grown man with an established career, it was terrifying. I shouldn’t have done it, but December has that magical power to make us that much more crazy. I drove home to Otterton, the Southern Ontario industrial town where I grew up, for a Saturday lunch visit, blasting trance music along the way loud enough to make the steering wheel shudder.

Mom gave me a Slender Nation shake, as usual, and after I drank it she offered me a sandwich, while Dad sat grimly across from me. His short black hair, still neatly combed, was starting to grey, and I detected a hunch beginning to form in his shoulders.

“The government,” he said, “is trying to destroy us.”

“I know Dad, you’ve told me that before.”

“You’ve got to be careful. Any day now, son, any day.” “Any day what?” I said, not sure if he was still talking of the government or had moved on to the Antichrist. The two were synonymous for him.

“They’ll be coming for us. We don’t have any good sense left in this country. We’ve got godless leaders. The States are doing much better—the new President Bush they’ve elected is a God-fearing man, he’ll set things right. We need someone like him up here.”

“Keith,” barked Mom. “We must focus on the spirit.” Mom adjusted her pink button, straightened her blouse, and instinctively touched her hair which, despite the years, remained as red as it was in my earliest memories of her.

“I am—this is all about the spirit. Everything is about the spirit,” he said through clenched teeth. He pointed at her and said, “You have no idea.”

“I have every idea,” she said. “Or at least the good ones. Stop your negativity, now, I command it in the blood of Jesus.” He wrung his hands at her and looked away. She turned to me, “Are you still drinking Slender Nation?” she said, her hands forming mirror C’s in front of her.

“Yes,” I said. “Actually, no. No I don’t. I only drink it when I’m here, when you’re in front of me, because that’s what you want me to do.”

“What are you saying?”

“I’m saying that I don’t drink Slender Nation anymore.” “But you had some just now.”

“I was being polite.”

“So dishonesty is politeness? That’s a lie, that’s sin. You need to pray for forgiveness, right now.”

“What would happen, William,” said Dad, “if The Rap- ture came right now? You’d be left behind. We need to pray, together, as a family.”

“No thanks,” I said, feeling a surge of total honesty, the kind of honesty that has nothing to do with what’s righteous or good. Righteousness may exist. And if it does, it moves quietly, anonymously, never calls itself by name.

“Please, let’s pray. This is dangerous,” said Mom, reaching for my hands.

“No.” I got up, backed away from her.

“What’s wrong with you?”

“Yes, what’s wrong with you?”

“Nothing. Nothing at all. For the first time in my life everything seems good, and you’re jumping all over me.” I wanted—oh so much—to show them my life, perhaps also to understand what had become of theirs, and desire drowned the logic that said I should keep silent and let them be.

“It’s a woman, isn’t it?” said Mom.

“The scarlet woman, God warns about her,” said Dad. Mom hit him. He sulked.

“It’s not a woman,” I said.

“So you don’t have a girlfriend, still, at your age?” “Which is it, Mom? Is it scary that I might have a girlfriend or is it weird that I don’t?”

“Don’t play games.”

“I’m not. I’m just trying to know where you stand.” “So, there’s a girl, then?”

“Actually, yes, there is a girl.”

“So it’s a woman, I knew it. Is she saved? Is she the one who led you away from Slender Nation?”

“Who is she? Where’s she from? Does she go to church?” Dad was back in the conversation.

“When do we meet her?” said Mom, raising her voice.

I waited two full breaths before speaking.

“Her name is Terry.” They were both leaning forward, looking at me, and in their eyes I saw the fear and hunger, that maniac desire from which I’d been on the run for most of my life.

"From Eulogy by Ken Murray, Tightrope Books 2015, ISBN: 9781926639857"

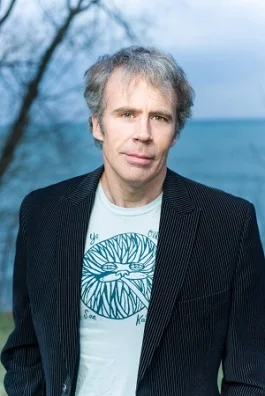

About the Author

KEN MURRAY is a writer and teacher of creative writing. His work has also appeared in Prairie Fire, Globe and Mail, Mendacity Review, Brooklyn Rail, Ottawa Citizen, Canadian Business Magazine, Maclean’s, and has also been published by the University of Toronto School of Continuing Studies (through the Random House of Canada Student Award in Writing). While earning his MFA at The New School, he also trained as a teaching artist with the Community Word Project and taught with Poets House. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including the inaugural Marina Nemat Award and the Random House Award, and received an Emerging Artist’s Grant from the Toronto Arts Council. Originally from Vancouver, Murray grew up in Ottawa and has lived across Canada and in New York City. He now divides his time between Prince Edward County and Haliburton Ontario, and teaches at the University of Toronto School of Continuing Studies and Haliburton School of the Arts.