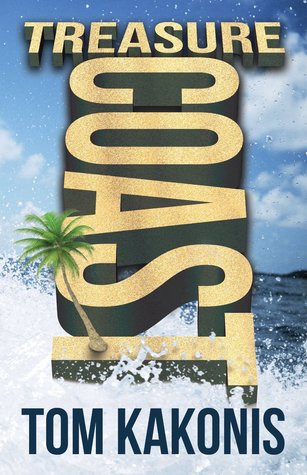

Excerpt from

TREASURE COAST

by

Tom Kakonis

LIKE MOST MEN CLOSING IN ON THE BENCHMARK

forty, Jim Merriman made far more promises—to others

mainly, a dwindling few yet to himself—than he knew, heart of

hearts, he ever intended to keep. It was a habit by now so deeply

entrenched, so much a part of him, that he wore it like a second

skin: Generate an earnest pledge today; effortlessly shuck

it off tomorrow. Mostly it was harmless, this habitual shortfall

between oath and execution, deed and good intention. A commonplace

human failing, to his thinking, small and forgivable.

A way of getting by in this sorry world.

But the vow exacted from him by a dying sister—that now

was giving him serious pause. Better make that acute discomfort.

(If he were going to be honest with himself, for a switch,

figuring—trying to figure—how to squirrel out of this one. Very

unsettling.)

From across the continent, he’d been summoned to her bed

of pain, where eventually, floating up out of a narcotized fog, she

found the strength to peel back crusted eyelids, fix him with a

fluttery gaze, and in a voice fainter than a whisper, feebler than a

gasp, murmur, “Jim? That you?”

“None other,” he affirmed, putting some of that fraudulent

deathwatch heartiness into it.

“You came.”

“Said I would.”

“Been here long?”

“Not long,” he lied. In fact he’d been sitting there for the better

part of the afternoon, studying her sleep, marveling at the

relentless progress of this formidable malady, its curious manifestations.

Her face, in sleep, was sunken, sallow with a greenish

tint, the color of mold-infested cheese. The sockets of the eyes,

hollow and dark, looked to be rimmed with a dusting of soot.

A limp hand, its flesh withered and veined as a dry leaf, seemed

to sprout from a forearm grotesquely swollen to Popeye proportions

and out of which coiled an IV vine that leaked some colorless,

powerless anodyne into her blood. Now that hand moved in

an effort at a sweeping gesture. “No, here, I mean. Florida.”

“I got in this morning. Leon picked me up at the airport.”

“Leon?”

“Yes.”

“Where is he?”

“Your place. I told him to go back and crash. He looked

pretty wasted.”

“It’s been hard for him,” she said.

“He’ll be OK.”

“You think so?”

“Sure.”

“I wonder.”

“How about you?” he asked. “They treating you right here?”

“They do what they can.”

“Well, you need anything, you just let me know,” he said,

more confidently than he felt—as if he had a direct hotline to the

nerve center of the AMA and could make the quacks jump at his

barked command. Hotline to nowhere was what he had.

She nodded dismally, said nothing.

To put something into the oppressive silence, he launched

a wandering monologue, picking his topics cautiously, from the

security of the distant past mostly, skirting that phantom third

presence in the room, Lord Death, with his constrictive time horizons.

“Remember that time…” he’d begin a tale, lifted from their

shared heartland childhood, and through the malleable prism of

inventive memory, he’d mutate some perfectly ordinary incident

into an adventure antic. Outrageously the tales grew in the telling,

spinning the sunny Leave It to Beaver mythology of a tight,

joyous, loving family life. Pure fabrication of course. All of it. The

sorry truth was that, apart from the accident of birth, they’d never

had much in common, never been particularly close. Nevertheless

he wore on, mouth running tirelessly, until at last the grab bag

of hilarious anecdotes was depleted, the memory-lane tour

exhausted, and again a desolate silence settled over the room.

Thee somber interval lengthened. After a while she filled it.

“Jim?”

“Yeah?”

Eyes tearing over, she said, not as a question, “There’s not

much time left, is there.”

“Oh, I don’t know about that. Nurse out there says you’re

holding your own.”

“Will you do something for me?” she asked, ignoring the blatant

falsehood.

“Whatever I can.”

“It’s Leon. He’s all alone now. So helpless. Like a child. Will

you watch out for him?”

“Sure, I’ll give the kid a hand” is what he told her. Another in

that legion of empty pledges. Slippery, purposely vague. The kind

of thing you search for to say. Should have been enough.

Except she couldn’t leave it alone. “Promise?”

“Hey, you can count on me,” he said lightly, conscious of the

sickly smile tacked on his face.

“Need to hear you say it, Jim.”

“Uh, what’s that?” he asked, stalling, averting his eyes from

that pleading, miseried gaze, unblinking now, insistent.

“You promise.”

So, cornered, he heard his voice utter that one too, the “p”

word, figuring, Why not? What’s the damage? Whatever it took

to help her exit gracefully, or as graceful as anyone riddled by

outlaw cells, wildly multiplying even as they spoke, could ever

exit. It was only words. Nothing lost, no one really hurt.

His first mistake. First of many.

Ten minutes later he stood outside the entrance to the Palm

Beach Gardens Medical Center, idly puffing a cigarette. A nurse,

briskly efficient, professionally cheery, her smile as starched as

her uniform, had appeared only a moment after the vow-taking

ceremony (nice timing, those mercy angels) and shooed him out

of the room, chirping something about “Time for meds” and

whatever other ghoulish things they did to keep the croakee

wheezing and earn their pay. OK by him. Welcome break from

the white world of the hospital and its clash of pungent perfumes,

its soiled bedsheets, lemony cleansing solutions, acrid antiseptics,

hothouse flowers, rank festering flesh.

The slanting rays of the sun, still fierce on an immense slate

of bleached sky, steamed the hospital lawn, glued the parking-lot

tar. The dank air resonated with the atonal hum of insect energy.

Symphony of famished worms, he thought ruefully, gathering for

the feast waiting just on the other side of this door.

A sudden mournful ache, hollow and unfocused, overtook

him. But whom did he really mourn? An expiring sister in there,

seldom seen, scarcely known, barely recognizable anymore, soon to

be floating out of herself? No, it was himself he sorrowed for, himself,

a couple of weeks short of a milestone birthday, half a lifetime

squandered, pissed away, and dying just as surely as she, only daily,

increment by increment, puff by puff . Conducting his own requiem

in advance, dirge supplied courtesy of an invisible swarm of bugs.

What they’re doing, these crusading nicotine zealots, by banishing

us from their haloed presence, he further reflected, dourly

now, is creating a breed of solitary, morbid philosophers. Seekers of

occult mystery in wisps of smoke.

His cigarette had grown a tail of ash. He ground it under a

heel, defiantly lit another. And just as he put a flame to it, a most

handsome woman clad in a satiny blouse and designer jeans came

through the door, paused, the shed a pack of Capris from a Gucci

bag slung over her shoulder, and shook one loose. The flame in

his hand still flickered, and so in that wordless bond that links

a renegade fraternity, he offered it to her. She favored him with

a small smile and ever so lightly touched his hand in a steadying

gesture. Fetching gesture, fetching smile. Up close this way,

he could see she wasn’t young but not yet old either, a ripened

thirtyish somewhere; by his best estimate, forty tops. Around a

plume of smoke, she said, “Another second-class citizen?”

“Afraid so.”

“They’re turning us into a bunch of sneaks.”

“Or worse yet, wimps. Where’s Bogie when we need him?”

“Who?” she asked.

“Humphrey Bogart. Remember him? Tough as nails, and he

always had a weed stuck in his face.”

“How about Bette Davis? Nobody crossed her.”

“There you are.”

One thing you had to give your habit—it was an instant icebreaker.

Something to be said for that, particularly when your

commiserator comes equipped with a dizzying cascade of platinum

curls; good bone geometry; skin lacquered to a high sheen;

a generous crimson-glossed mouth; eyes a cool blue but with a

glint of worldly mischief in them; and pliant, slightly plumpish

curves under a fashion-statement outfit. Like this one did. All

of which he assimilated in a sly sidelong glance, as he no longer

pondered his own mortality but rather the enduring quality of

lust, how it occasionally nods but never really sleeps.

“You visiting somebody?” she asked him, turning the talk

elsewhere, extending it. Promising signal.

“A sister,” Jim said.

“Is it serious?”

“It’s cancer.”

“Bad?”

“Terminal variety.”

“That’s a shame.”

He shrugged. “Yeah, well, cancer always wins.”

She took a long, meditative pull on her Capri. the third finger

of the cigarette-bearing hand, he noticed, was bedecked with

a gaudy rock the size of a boulder. Generally—though not absolutely,

in his experience—a bad signal. In a stagy, breathy voice,

she said, “I’m real sorry.”

“No need to be,” he said with mock solemnity. “Doctors

determined it wasn’t your fault.”

For a sliver of an instant, she looked perplexed. Then, as she

got it, her smile widened, displaying an abundance of teeth, dazzling

as neon and much too perfect to be anything but orthodontist

enhanced. Jim gave her back his player smile, oblique,

distant, hint of evasiveness in it. Dueling grins.

Hers departed first, displaced by an earnest expression. “Is

she centered?”

“Centered?”

“Centered,” she repeated, as though the echo explained itself.

“Afraid I don’t follow,” he said, baffled by the corkscrew twist

in the conversation and wondering if maybe this time the joke

wasn’t on him.

“Like, in tune with her spiritual center.”

Evidently no joke. “Well,” he said, “we’ve never been what

you’d call God-fearing people. She taught math, some community

college down here. Numbers are—were—her religion.”

“Got nothing to do with religion,” she declared, a little impatiently.

“No? What then?”

“Energy. Strictly energy. See, I read this book by this Indian

guy—from India, I mean, not your American kind—where he

shows how we’re all a part of this one big spirit. Only he calls

it energy. Cosmic energy. And it’s, like, steady. Never changes,

never dies. What we call ‘dying’ is just trading energies.”

“That’s a comfort.”

“And what you got to do,” she plowed on, voice elevating

urgently, “when your body’s ready to pass, is zero in on it, your

place in this energy field. That’s what centering is. Sort of like

finding your way home.”

“Interesting theory,” Jim allowed, thinking they all have to

come with some wart, physical or otherwise. Even the best of

them, like this dumpling of sex here, with the loopy-energy hair

up her sweet apple ass. Too bad. Terrible waste.

“Changed my life, I can tell you.”

“Bet it did at that.”

“What I do now,” she said, “is try and help people get in

touch with it. Their energy center. That’s why I’m here. My best

girlfriend’s mother—she’s about to pass too.”

Sounded to him like some spiritual fart cutting, with her

being the therapeutic Gas-X. But what he said was, “Sounds sort

of like volunteer work.”

“Guess you could call it that. See, growing up, I wanted to be

a nurse. Never did make it, so this is the next best thing.”

“You? A nurse?”

“I always wanted to help people.”

Yeah, right. “I see,” he said cautiously, radar suddenly alert

for a scam coming on.

“So you think she’s centered yet?”

“Who’s that?”

“Who we’re talking about here…your sis.”

“You got me.”

“If you want, I could speak to her.”

Finally the pitch. Everybody peddling something. Pretty

prosperous clip too, by the looks of that stone weighting her

finger. Unless, of course, it was fake. “Appreciate the offer,” Jim

said, “but I don’t think she’d be very receptive.” Figured that’d

be the end of it. Any good fleecer knows when it’s time to

book.

Figured wrong. “OK,” she said breezily and, in yet another

of those bootleg turns, added, “You’re not from around here, are

you?”

“How could you tell?”

“Wild guess.”

“You guessed right.”

“Whereabouts then?”

“Nevada.”

“Vegas?”

“Reno.”

“Reno, Vegas—they’re like Florida,” she said. “Nobody’s

from there.”

“Right again.”

“So? Originally where?”

“South Dakota.”

“No kidding!” she exclaimed. “Me too. I’m from Bismark.”

“That’s in North Dakota.”

“Same thing.”

“I expect maybe it is. There’s not all that many of us, either

province.”

“Hey, don’t I know? That’s why we got to stick together. What

I always say is, ‘When you’re from Dakota, you got to be good.’ ”

Jim regarded her narrowly. A corner of her wide mouth was

lifted once again in a suggestion of a smile, artful, provocative,

faintly amused. The naughty mischief he’d seen earlier, thought

he’d seen, all but given up on during the energy drone, shimmered

behind her eyes. “By that,” he said, choosing his words

carefully (for if four decades had taught him any lesson at all, it

was that a man never knew when he was going to get lucky), “do

you mean ‘nice good’? Or oh, say, ‘skillful good,’ ‘accomplished’?”

Before she could reply, a sleek silver Porsche swung into the

lot and lurched to an idling stop twenty or so yards from where

they stood. A head—male, jowly, squinty eyed, round, and hairless

as a billiard ball—poked out of the driver’s-side window like

a wary turtle emerging from its shell. She gave it a high-handed

wave, a big theatrical welcoming grin, calling, “Hi, honey. Be

right with you.” To Jim she stage-whispered, “Thee big doolie

arrives.”

“Doolie?”

“The worse half.”

“Oh.”

She lowered the waving hand, abruptly thrust it at him.

“Been real nice talking to you.”

Jim took the offered hand. Grip was surprisingly firm; the

shake snappy, businesslike. “Same here,” he said.

“My name’s Billie. Billie Swett.”

“Swett?”

“You got it. Like in the perspiration, only with an ‘e’ and two

‘t’s. Cute, huh?”

“Well, everybody’s got to be named something.”

“And you are?”

“Jim Merriman.”

“Merriman,” she repeated, the tantalizing shimmer not quite

gone out of her eyes. “You don’t look so merry to me.”

“Inside I’m laughing.”

“Listen, you change your mind—about your sister, I mean—

I’ll be at the hospital here. Next couple days anyway. Ask around.

They know me in there.”

“I’ll be watching.”

The Porsche’s horn bleated. The turtle head squawked,

“C’mon, honey. We’re runnin’ late.”

“I’m coming, hon,” she called back sweetly, but under her

breath, softly, though not so soft as to be inaudible, she muttered,

“Asshole.”

Across lawn and lot, she sauntered, loose easy stride, studied

sway in the shapely hips. Into the Porsche she climbed, pecked

the turtle on the cheek, checked her reflection in the rearview,

patted and primped the cotton candy ringlets. And with that the

two honeys were gone, sped away, leaving Jim to speculate now

on the quirky nature of luck, which, he suspected, like gold, was where you found it.

Excerpted from the book TREASURE COAST by Tom Kakonis. Copyright © 2014 by Tom Kakonis. Reprinted with permission of Brash Books. All rights reserved