People Live Inside Us by Sharman Russell

/People live inside us. Sometimes we talk to these people, and sometimes they answer back. Sometimes they are simply a presence, almost a dream, living in the darkness of the body. Sometimes they are four hundred years old, sun-blistered, whip-thin, speaking the Spanish dialect of sixteenth-century Seville—which would be the case with the real-life conquistador Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, a man who has intrigued me for decades, whose story I have read over and over, whom I have written about again and again, and who finally set up camp in my frontal lobe, roasting fish and roots, sketching maps in the sand, praying, scheming, surviving—as indomitable as a gust of wind, sea, and salt.

In 1528, Cabeza de Vaca was the Spanish treasurer of the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition which sailed into Tampa Bay, Florida with four ships, four hundred men, ten women, and eighty horses. Led by the incompetent Narváez, the men marched inland, got lost, built barges, limped along the Gulf of Mexico coastline, and shipwrecked near present-day Galveston Island. Almost everyone died. Among the diverse tribes of Texas, however, Cabeza de Vaca found new employment as a slave, healer, and trader. For eight years, naked and hungry, he was stripped of his identity and past. Finally he and three other former conquistadors began to walk west to the outposts of New Spain. They became known as the Children of the Sun, strangers who could heal the sick and raise the dead in an extraordinary traveling medicine man show that was orchestrated and accompanied by thousands of Native American followers. In northwestern Mexico, the Children of the Sun met up with Spanish slave hunters who promptly captured these followers and sent Cabeza de Vaca and his companions on to Mexico City and eventually back to Spain. In 1542, Cabeza de Vaca published his story as a report to the king of Spain, the first European description of the New World, rich with anthropological detail and a final plea to meet the natives “with kindness, the only certain way.”

For over four hundred years, we have interpreted the journey of Cabeza de Vaca—in numerous translations of his report to the king of Spain, in fictional accounts, and in film. For some of us, he is the first American adventure-hero telling the first American tale. He is our Odysseus, saint and sinner, mystic and conqueror rolled into one. From the perspective of Native America, he is part of a great and terrible transformation, their world overturned by new diseases and technologies. First Contact. The “Old” and “New” meet in this story, and nothing is ever the same.

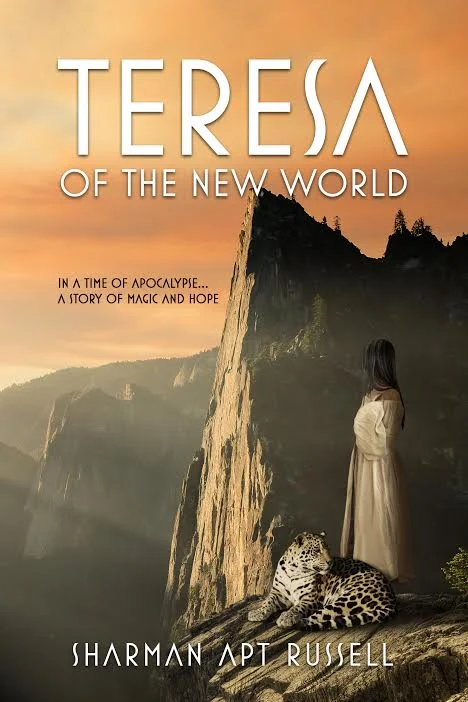

My new young adult novel Teresa of the New World is the culmination of my long-time fascination with Cabeza de Vaca, whom I first wrote about in 1996 in the collection of essays When the Land was Young: Reflections on American Archaeology. Earlier, I had written about him in a literary adult novel, a manuscript I eventually abandoned, compressing most of its 300 pages into the first 40 pages of a book for young adults. In this new version, the sixteenth century of the American Southwest is a dreamscape of shape-shifters and loss and beauty. As the daughter of Cabeza de Vaca and a Capoque mother, Teresa is betrayed by her hero-father, sent to live as a kitchen servant in the household of a Spanish official, and alienated from the magic she knew as a child when she could listen to plants and animals and sink into the trickster earth. Plague stalks the land. Measles decimates native villages. And Teresa goes on her own journey, befriending a Spanish war horse and were-jaguar as she struggles to reclaim her power and sense of self.

But what surprised me is this: just as the book was being printed, when my publisher asked if I wanted a dedication page, I emailed back—as though this were an afterthought—yes, “To my father.” It had taken me thirty years to write this book and as long to see how much I am Teresa and how much my father is Cabeza de Vaca--which is really a statement about the un in my unconscious. Or maybe, stranger, I am Cabeza de Vaca and my father, that young, heroic test pilot from Kansas, is Teresa. And really, strangest still, I am neither Teresa nor Cabeza de Vaca; instead they are people who live inside me. They have their own life, even as they have enriched mine.

About Sharman Russell

Sharman Apt Russell has lived in Southwestern deserts almost all her life and continues to be refreshed and amazed by the magic and beauty of this landscape. She has published over a dozen books translated into a dozen languages, including fiction and nonfiction. She teaches graduate writing classes at Western New Mexico University in Silver City, New Mexico and Antioch University in Los Angeles, California and has thrice served as the PEN West judge for their annual children’s literature award. Her own awards include a Rockefeller Fellowship, the Mountains and Plains Booksellers Award, a Pushcart Prize, and the Henry Joseph Jackson Award.

For more information visit Sharman Russell’s website. You can also find her on Facebook and Goodreads.

About Teresa of the New World

From the bestselling author of An Obsession with Butterflies comes a magical story of America in the time of the conquistadors.

In 1528, the real-life conquistador Cabeza de Vaca shipwrecked in the New World where he lived for eight years as a slave, trader, and shaman. In this lyrical weaving of history and myth, the adventurer takes his young daughter Teresa from her home in Texas to walk westward into the setting sun, their travels accompanied by miracles–visions and prophecies. But when Teresa reaches the outposts of New Spain, life is not what her father had promised.

As a kitchen servant in the household of a Spanish official, Teresa grows up estranged from the magic she knew as a child, when she could speak to the earth and listen to animals. When a new epidemic of measles devastates the area, the sixteen-year-old sets off on her own journey, befriending a Mayan were-jaguar who cannot control his shape-shifting and a warhorse abandoned by his Spanish owner. Now Teresa moves through a land stalked by Plague: smallpox as well as measles, typhus, and scarlet fever.

Soon it becomes clear that Teresa and her friends are being manipulated and driven by forces they do not understand. To save herself and others, Teresa will find herself listening again to the earth, sinking underground, swimming through limestone and fossil, opening to the power of root and stone. As she searches for her place in the New World, she will travel farther and deeper than she had ever imagined.

Rich in historical detail and scope, Teresa of the New World takes you into the dreamscape of the sixteenth-century American Southwest.